Git from the inside out

This essay explains how Git works. It assumes you understand Git well enough to use it to version control your projects.

The essay focuses on the graph structure that underpins Git and how the properties of this graph dictate Git’s behavior. This focus on fundamentals lets you build your mental model on the truth, rather than on hypotheses constructed from evidence gathered while experimenting with the API. This truer model gives you a better understanding of what Git has done, what it is doing, and what it will do.

The text is structured as a series of Git commands run on a single project. At intervals, there are observations about the graph data structure that Git is built on. These observations illustrate a property of the graph and the behavior that this property produces.

After reading, if you wish to go even deeper into Git, you can look at the heavily annotated source code of Gitlet, my implementation of Git in JavaScript.

Create the project

~ $ mkdir alpha

~ $ cd alpha

The user creates

alpha, a directory for their project.~/alpha $ mkdir data

~/alpha $ printf 'a' > data/letter.txt

They move into the

alpha directory and create a directory called data. Inside, they create a file called letter.txt that contains a. The alpha directory looks like this:alpha

└── data

└── letter.txt

Initialize the repository

~/alpha $ git init

Initialized empty Git repository

git init makes the current directory into a Git repository. To do this, it creates a .gitdirectory and writes some files to it. These files define everything about the Git configuration and history of the project. They are just ordinary files. No magic in them. The user can read and edit them with a text editor or shell. Which is to say: the user can read and edit the history of their project as easily as their project files.

The

alpha directory now looks like this:alpha

├── data

| └── letter.txt

└── .git

├── objects

etc...

The

.git directory and its contents are Git’s. All the other files are collectively known as the working copy. They are the user’s.Add some files

~/alpha $ git add data/letter.txt

The user runs

git add on data/letter.txt. This has two effects.

First, it creates a new blob file in the

.git/objects/ directory.

This blob file contains the compressed content of

data/letter.txt. Its name is derived by hashing its content. Hashing a piece of text means running a program on it that turns it into a smaller1 piece of text that uniquely2 identifies the original. For example, Git hashes a to 5e40c0877058c504203932e5136051cf3cd3519b. The first two characters are used as the name of a directory inside the objects database: .git/objects/5e/. The rest of the hash is used as the name of the blob file that holds the content of the added file:.git/objects/5e/40c0877058c504203932e5136051cf3cd3519b.

Notice how just adding a file to Git saves its content to the

objects directory. If the user were to delete data/letter.txt from the working copy, its content would still be safe inside Git.

Second,

git add adds the file to the index. The index is a list that contains every file that Git has been told to keep track of. It is stored as a file at .git/index. Each line of the file maps a tracked file to the hash of its content at the moment it was added. This is the index after the git add command is run:data/letter.txt 5e40c0877058c504203932e5136051cf3cd3519b

The user makes a file called

data/number.txt that contains 1234.~/alpha $ printf '1234' > data/number.txt

The working copy looks like this:

alpha

└── data

└── letter.txt

└── number.txt

The user adds the file to Git.

~/alpha $ git add data

The

git add command creates a blob object that contains the content ofdata/number.txt. And it adds an index entry for data/number.txt that points the blob. This is the index after the git add command is run a second time:data/letter.txt 5e40c0877058c504203932e5136051cf3cd3519b

data/number.txt 274c0052dd5408f8ae2bc8440029ff67d79bc5c3

Notice that, though the user ran

git add data, only the files in the data directory are listed in the index. The data directory is not listed separately.~/alpha $ printf '1' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data

When the user originally created

data/number.txt, they meant to type 1, not 1234. They make the correction and add the file to the index again. This command creates a new blob with the new content. And it updates the index entry for data/number.txt to point at the new blob.Make a commit

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'a1'

[master (root-commit) c388d51] a1

The user makes the

a1 commit. Git prints some data about the commit. These data will make sense shortly.

The commit command has three steps. It creates a tree graph to represent the content of the version of the project being committed. It creates a commit object. It points the current branch at the new commit object.

Create a tree graph

Git records the current state of the project by creating a tree graph from the index. This tree graph records the location and content of every file in the project.

The graph is composed of two types of object: blobs and trees.

Blobs are stored by

git add. They represent the content of files.

Trees are stored when a commit is made. A tree represents a directory in the working copy.

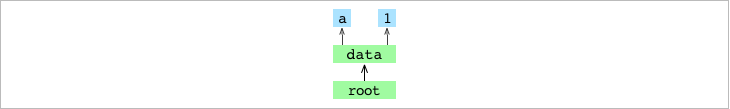

Below is the tree object that records the contents of the

data directory for the new commit:100664 blob 5e40c0877058c504203932e5136051cf3cd3519b letter.txt

100664 blob 274c0052dd5408f8ae2bc8440029ff67d79bc5c3 number.txt

The first line records everything required to reproduce

data/letter.txt. The first part states the file’s permissions. The second part states that the content of this entry is represented by a blob, rather than a tree. The third part states the hash of the blob. The fourth part states the file’s name.

The second line records the same for

data/number.txt.

Below is the tree object for

alpha, the root directory of the project:040000 tree 0eed1217a2947f4930583229987d90fe5e8e0b74 data

The sole line in this tree points at the

data tree.

Tree graph for the

a1 commit

In the graph above, the

alpha tree points at the data tree. The data tree points at the blobs for data/letter.txt and data/number.txt.Create a commit object

After creating the tree graph,

git commit creates a commit object. This is just another text file in .git/objects/:tree ffe298c3ce8bb07326f888907996eaa48d266db4

author Mary Rose Cook <mary@maryrosecook.com> 1424798436 -0500

committer Mary Rose Cook <mary@maryrosecook.com> 1424798436 -0500

a1

The first line points at the tree graph. The hash is for the tree object that represents the root of the working copy. That is: the

alpha directory. The last line is the commit message.

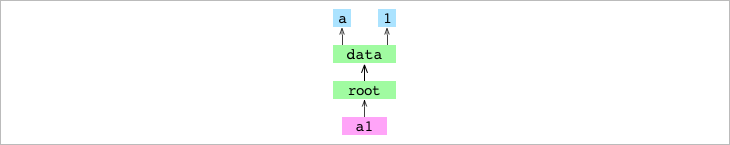

a1 commit object pointing at its tree graphPoint the current branch at the new commit

Finally, the commit command points the current branch at the new commit object.

Which is the current branch? To find out, Git goes to the

HEAD file at .git/HEAD and finds:ref: refs/heads/master

This says that

HEAD is pointing at master. master is the current branch.HEAD and master are both refs. A ref is a label used by Git or the user to identify a specific commit.

The file that represents the

master ref does not exist, because this is the first commit to the repository. Git creates the file at .git/refs/heads/master and sets its content to the hash of the commit object:a87cc0f39d12e51be8d68eab5cef1d31e8807a1c

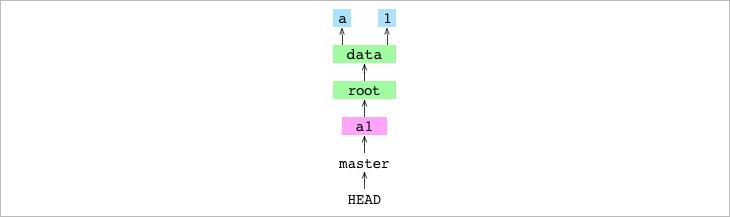

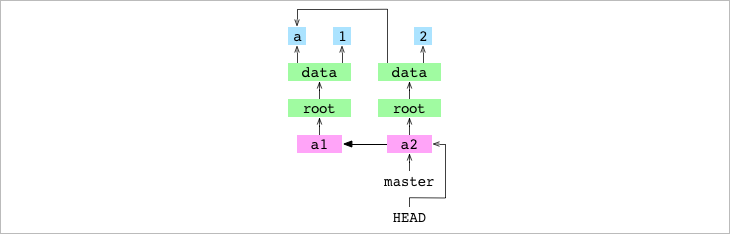

Let’s add

HEAD and master to the Git graph:

HEAD pointing at master and master pointing at the a1 commitHEAD points at master, as it did before the commit. But master now exists and points at the new commit object.Make a commit that is not the first commit

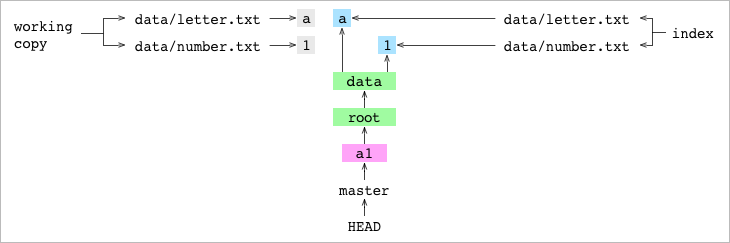

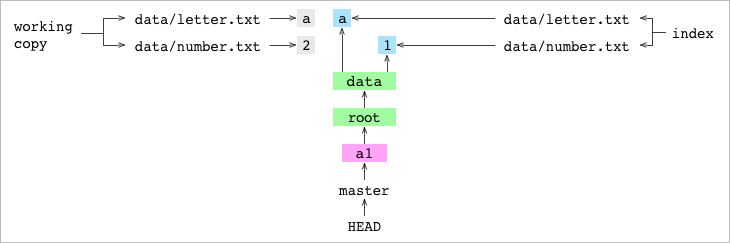

Below is the Git graph after the

a1 commit. The working copy and index are included.

a1 commit shown with the working copy and index

Notice that the working copy, index, and

a1 commit all have the same content fordata/letter.txt and data/number.txt. Notice that the index and HEAD commit both use hashes to refer to blob objects, but the working copy content is stored as text in a different place.~/alpha $ printf '2' > data/number.txt

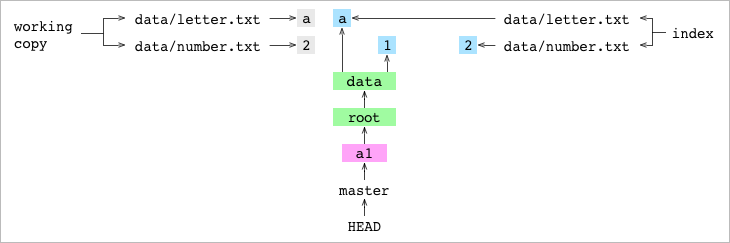

The user sets the content of

data/number.txt to 2. This updates the working copy, but leaves the index and HEAD commit as they are.

data/number.txt set to 2 in the working copy~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

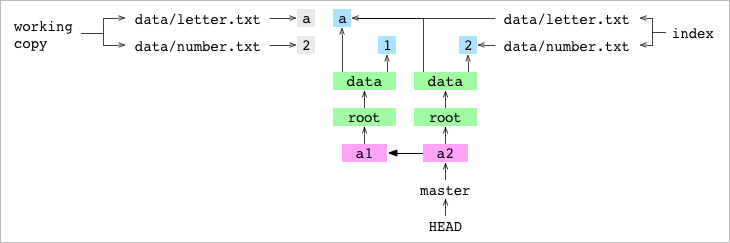

The user adds the file to Git. This adds a blob containing

2 to the objects directory. And it points the index entry for data/number.txt at the new blob.

data/number.txt set to 2 in the working copy and index~/alpha $ git commit -m 'a2'

[master ae78f19] a2

The user commits. The steps for the commit are the same as before.

First, a new tree graph is created to represent the content of the index.

The index entry for

data/number.txt has changed. The old data tree no longer reflects the indexed state of the data directory. A new data tree object must be created:100664 blob 2e65efe2a145dda7ee51d1741299f848e5bf752e letter.txt

100664 blob d8263ee9860594d2806b0dfd1bfd17528b0ba2a4 number.txt

The new

data tree hashes to a value that is different from the old data tree. A newalpha tree must be created to record this hash:040000 tree 40b0318811470aaacc577485777d7a6780e51f0b data

Second, a new commit object is created.

tree ce72afb5ff229a39f6cce47b00d1b0ed60fe3556

parent 30ec3334aaa3954ef44fb6b68cfbf1a225c3d5af

author Mary Rose Cook <mary@maryrosecook.com> 1424813101 -0500

committer Mary Rose Cook <mary@maryrosecook.com> 1424813101 -0500

a2

The first line of the commit object points at the new

alpha tree object. The second line points at the commit’s parent, a1. To find the parent commit, Git went to HEAD, followed it to master and found the commit hash of a1.

Third, the content of the

master branch file is set to the hash of the new commit.

a2 commit

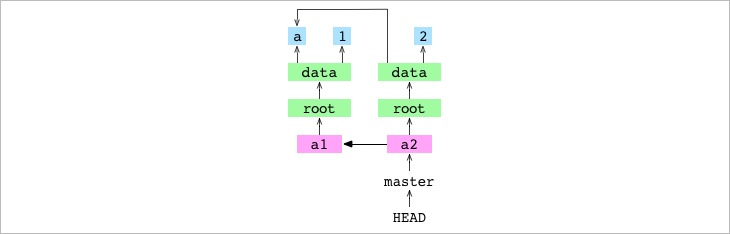

Git graph without the working copy and index

Graph property: content is stored as a tree of objects. This means that only diffs are stored in the objects database. Look at the graph above. The

a2 commit reuses the ablob that was made before the a1 commit. Similarly, if a whole directory doesn’t change from commit to commit, its tree and all the blobs and trees below it can be reused. Generally, there are few content changes from commit to commit. This means that Git can store large commit histories in a small amount of space.

Graph property: each commit has a parent. This means that a repository can store the history of a project.

Graph property: refs are entry points to one part of the commit history or another. This means that commits can be given meaningful names. The user organizes their work into lineages that are meaningful to their project with concrete refs like

fix-for-bug-376. Git uses symbolic refs like HEAD, MERGE_HEAD and FETCH_HEAD to support commands that manipulate the commit history.

Graph property: the nodes in the

objects/ directory are immutable. This means that content is edited, not deleted. Every piece of content ever added and every commit ever made is somewhere in the objects directory3.

Graph property: refs are mutable. Therefore, the meaning of a ref can change. The commit that

master points at might be the best version of a project at the moment, but, soon enough, it will be superseded by a newer and better commit.

Graph property: the working copy and the commits pointed at by refs are readily available, but other commits are not. This means that recent history is easier to recall, but that it also changes more often. Or: Git has a fading memory that must be jogged with increasingly vicious prods.

The working copy is the easiest point in history to recall because it is in the root of the repository. Recalling it doesn’t even require a Git command. It is also the least permanent point in history. The user can make a dozen versions of a file, but, unless they are added, Git won’t record any of them.

The commit that

HEAD points at is very easy to recall. It is at the tip of the branch that is checked out. To see its content, the user can just stash4 and then examine the working copy. At the same time, HEAD is the most frequently changing ref.

The commit that a concrete ref points at is easy to recall. The user can simply check out that branch. The tip of a branch changes less often than

HEAD, but still often enough for the meaning of a branch name to be changeable.

It is difficult to recall a commit that is not pointed at by any ref. And, the further the user goes from a ref, the harder it will be for them to construct the meaning of a commit. But, the further back they go, the less likely it is that someone will have changed history since they last looked5.

Check out a commit

~/alpha $ git checkout 37888c2

You are in 'detached HEAD' state...

The user checks out the

a2 commit using its hash. (If you are running these Git commands, this one won’t work. Use git log to find the hash of your a2 commit.)

Checking out has four steps.

First, Git gets the

a2 commit and gets the tree graph it points at.

Second, it writes the file entries in the tree graph to the working copy. This results in no changes. Because

HEAD was already pointing (via master) at the a2 commit, the working copy already has the content of the tree graph being written to it.

Third, Git writes the file entries in the tree graph to the index. This, too, results in no changes. The index already has the content of the

a2 commit.

Fourth, the content of

HEAD is set to the hash of the a2 commit:37888c274ecb894b656829d55e88cd086c9b2f72

Setting the content of

HEAD to a hash puts the repository in the detached HEAD state. Notice in the graph below that HEAD, rather than pointing at master, points directly at the a2 commit.

Detached

HEAD on a2 commit~/alpha $ printf '3' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

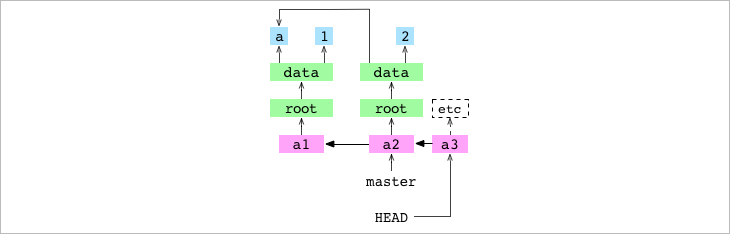

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'a3'

[detached HEAD 05f9ae6] a3

The user sets the content of

data/number.txt to 3 and commits the change. To get the parent of the a3 commit, Git goes to HEAD. Instead of finding and following a branch ref, it finds and returns the hash of the a2 commit.

Git updates

HEAD to point directly at the hash of the new a3 commit. The repository is still in the detached HEAD state. Because no commit points at either a3 or one of its descendants, it is not on a branch. This means it is easy to lose.

Note that, from now on, trees and blobs will mostly be omitted from the graph diagrams.

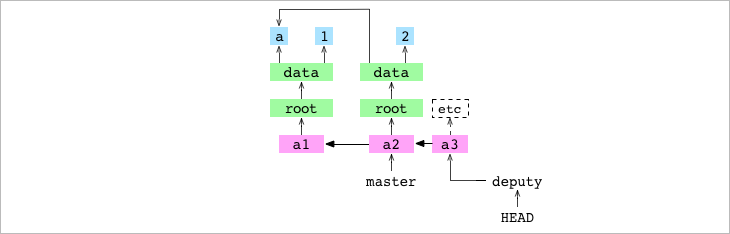

a3 commit that is not on a branchCreate a branch

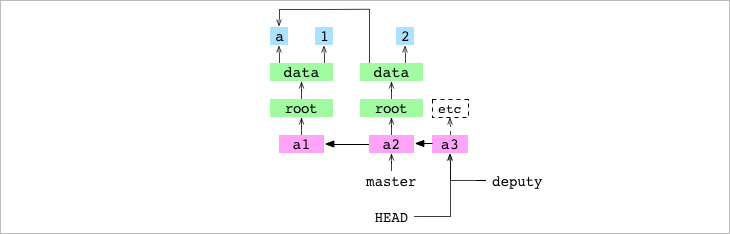

~/alpha $ git branch deputy

The user creates a new branch called

deputy. This just creates a new file at.git/refs/heads/deputy that contains the hash that HEAD is pointing at. That is, the hash of the a3 commit.

Graph property: branches are just refs and refs are just files. This means that Git branches are lightweight.

The creation of the

deputy branch puts the new a3 commit safely on a branch. HEAD is still detached because it still points directly at a commit.

a3 commit now on the deputy branchCheck out a branch

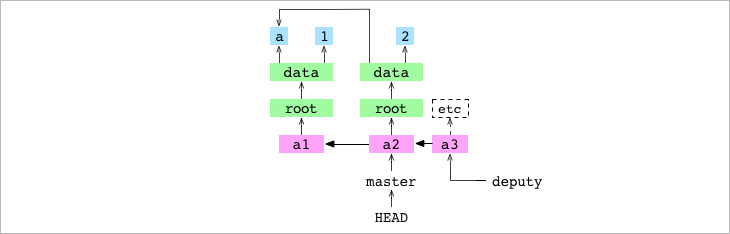

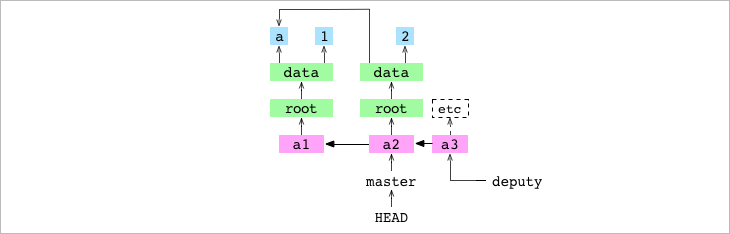

~/alpha $ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

The user checks out the

master branch.

First, Git gets the

a2 commit that master points at and gets the tree graph the commit points at.

Second, Git writes the file entries in the tree graph to the files of the working copy. This sets the content of

data/number.txt to 2.

Third, Git writes the file entries in the tree graph to the index. This updates the entry for

data/number.txt to the hash of the 2 blob.

Fourth, Git points

HEAD at master by changing its content from a hash to:ref: refs/heads/master

master checked out and pointing at the a2 commitCheck out a branch that is incompatible with the working copy

~/alpha $ printf '789' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git checkout deputy

Your changes to these files would be overwritten

by checkout:

data/number.txt

Commit your changes or stash them before you

switch branches.

The user accidentally sets the content of

data/number.txt to 789. They try to check outdeputy. Git prevents the check out.HEAD points at master which points at a2 where data/number.txt reads 2. deputypoints at a3 where data/number.txt reads 3. The working copy version ofdata/number.txt reads 789. All these versions are different and they must be resolved.

Git could replace the working copy version of

data/number.txt with the version in the commit being checked out. But it avoids data loss at all costs.

Git could merge the working copy version with the version being checked out. But this is complicated.

So, Git aborts the check out.

~/alpha $ printf '2' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git checkout deputy

Switched to branch 'deputy'

The user notices that they accidentally edited

data/number.txt and sets the content back to 2. They check out deputy successfully.

deputy checked outMerge an ancestor

~/alpha $ git merge master

Already up-to-date.

The user merges

master into deputy. Merging two branches means merging two commits. The first commit is the one that deputy points at: the receiver. The second commit is the one that master points at: the giver. For this merge, Git does nothing, reporting it is Already up-to-date..

Graph property: the series of commits in the graph are interpreted as a series of changes made to the content of the repository. This means that, in a merge, if the giver commit is an ancestor of the receiver commit, Git will do nothing. Those changes have already been incorporated.

Merge a descendent

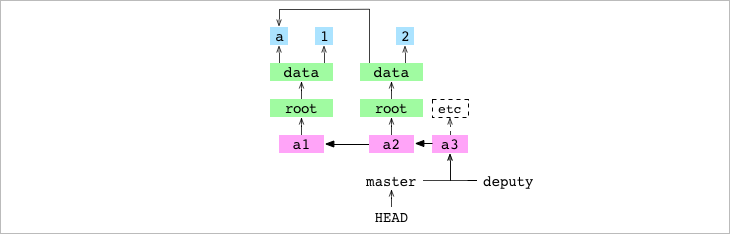

~/alpha $ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

The user checks out

master.

master checked out and pointing at the a2 commit~/alpha $ git merge deputy

Fast-forward

They merge

deputy into master. Git discovers that the receiver commit, a2, is an ancestor of the giver commit, a3. This means it can do a fast-forward merge.

It gets the giver commit and gets the tree graph that it points at. It writes the file entries in the tree graph to the working copy and the index. It “fast-forwards”

master to point at a3.

a3 commit from deputy fast-forward merged into master

Graph property: the series of commits in the graph are interpreted as a series of changes made to the content of the repository. This means that, in a merge, if the giver is a descendent of the receiver, history is not changed. There is already a sequence of commits that describe the change to make: the sequence of commits between the receiver and the giver. But, though the Git history doesn’t change, the Git graph does change. The concrete ref that

HEAD points at is updated to point at the giver commit.Merge two commits from different lineages

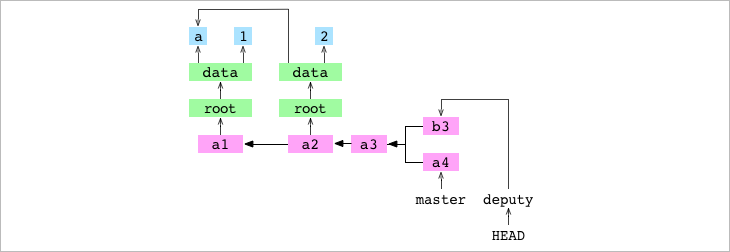

~/alpha $ printf '4' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'a4'

[master c6b955e] a4

The user sets the content of

number.txt to 4 and commits the change to master.~/alpha $ git checkout deputy

Switched to branch 'deputy'

~/alpha $ printf 'b' > data/letter.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/letter.txt

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'b3'

[deputy d75b998] b3

The user checks out

deputy. They set the content of data/letter.txt to b and commit the change to deputy.

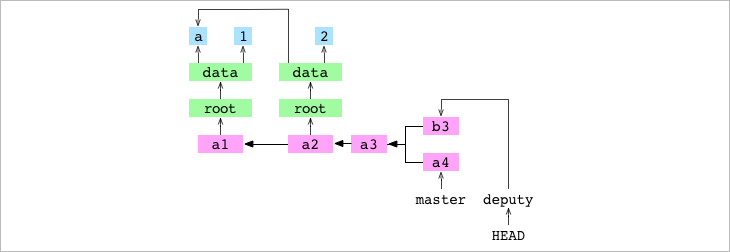

a4 committed to master, b3 committed to deputy and deputy checked out

Graph property: commits can share parents. This means that new lineages can be created in the commit history.

Graph property: commits can have multiple parents. This means that separate lineages can be joined by a commit with two parents: a merge commit.

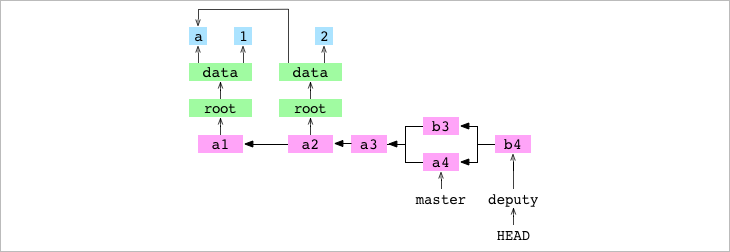

~/alpha $ git merge master -m 'b4'

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

The user merges

master into deputy.

Git discovers that the receiver,

b3, and the giver, a4, are in different lineages. It makes a merge commit. This process has eight steps.

First, Git writes the hash of the giver commit to a file at

alpha/.git/MERGE_HEAD. The presence of this file tells Git it is in the middle of merging.

Second, Git finds the base commit: the most recent ancestor that the receiver and giver commits have in common.

a3, the base commit of a4 and b3

Graph property: commits have parents. This means that it is possible to find the point at which two lineages diverged. Git traces backwards from

b3 to find all its ancestors and backwards from a4 to find all its ancestors. It finds the most recent ancestor shared by both lineages, a3. This is the base commit.

Third, Git generates the indices for the base, receiver and giver commits from their tree graphs.

Fourth, Git generates a diff that contains the changes required to go from the content of the receiver commit to the content of the giver commit. This diff is a list of file paths that point to a change: add, remove, modify or conflict.

Git gets the list of all the files that appear in the base, receiver or giver indices. For each one, it compares the index entries to find the change that was made to the file. It writes a corresponding entry to the diff. In this case, the diff has two entries.

The first entry is for

data/letter.txt. The content of this file is a in the base, b in the receiver and a in the giver. The content is different in the base and receiver. But it is the same in the base and giver. Git sees that the content was modified by the receiver, but not the giver. The diff entry for data/letter.txt is a modification, not a conflict.

The second entry in the diff is for

data/number.txt. In this case, the content is the same in the base and receiver, and different in the giver. The diff entry for data/letter.txt is also a modification.

Graph property: it is possible to find the base commit of a merge. This means that, if a file has changed from the base in just the receiver or giver, Git can automatically resolve the merge of that file. This reduces the work the user must do.

Fifth, the changes indicated by the entries in the diff are applied to the working copy. The content of

data/letter.txt is set to b and the content of data/number.txt is set to4.

Sixth, the changes indicated by the entries in the diff are applied to the index. The entry for

data/letter.txt is pointed at the b blob and the entry for data/number.txt is pointed at the 4 blob.

Seventh, the updated index is committed:

tree 20294508aea3fb6f05fcc49adaecc2e6d60f7e7d

parent d75b9983183df12a8e745318d0c31cc1782eaf2f

parent c6b955e6d3d26248112b29176d47b4186a9a20c8

author Mary Rose Cook <mary@maryrosecook.com> 1425596551 -0500

committer Mary Rose Cook <mary@maryrosecook.com> 1425596551 -0500

b4

Notice that the commit has two parents.

Eighth, Git points the current branch,

deputy, at the new commit.

b4, the merge commit resulting from the recursive merge of a4 into b3Merge two commits from different lineages that both modify the same file

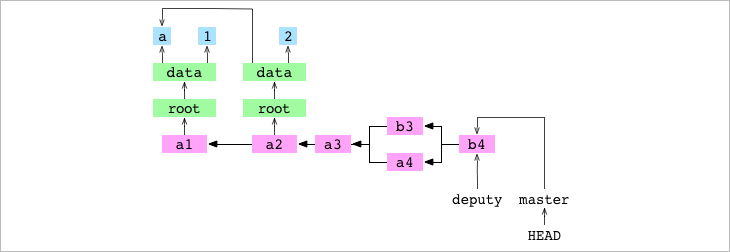

~/alpha $ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

~/alpha $ git merge deputy

Fast-forward

The user checks out

master. They merge deputy into master. This fast-forwards masterto the b4 commit. master and deputy now point at the same commit.

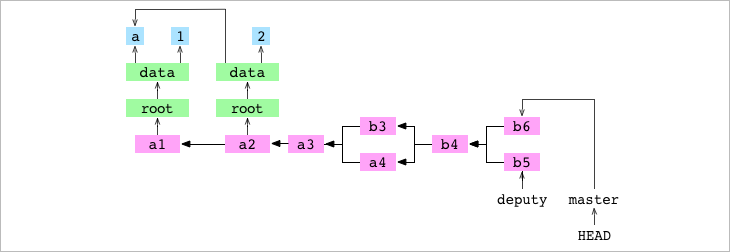

deputy merged into master to bring master up to the latest commit, b4~/alpha $ git checkout deputy

Switched to branch 'deputy'

~/alpha $ printf '5' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'b5'

[deputy 15b9e42] b5

The user checks out

deputy. They set the content of data/number.txt to 5 and commit the change to deputy.~/alpha $ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

~/alpha $ printf '6' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'b6'

[master 6deded9] b6

The user checks out

master. They set the content of data/number.txt to 6 and commit the change to master.

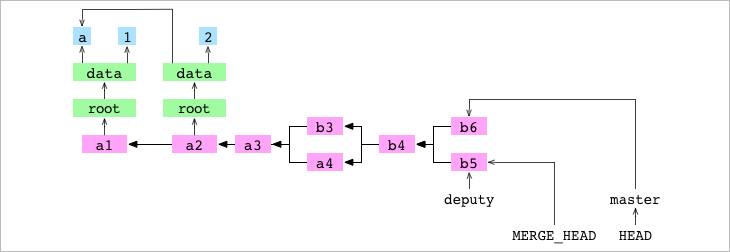

b5 commit on deputy and b6 commit on master~/alpha $ git merge deputy

CONFLICT in data/number.txt

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and

commit the result.

The user merges

deputy into master. There is a conflict and the merge is paused. The process for a conflicted merge follows the same first six steps as the process for an unconflicted merge: set .git/MERGE_HEAD, find the base commit, generate the indices of the base, receiver and giver commits, create a diff, update the working copy and update the index. Because of the conflict, the seventh commit step and eighth ref update step are never taken. Let’s go through the steps again and see what happens.

First, Git writes the hash of the giver commit to a file at

.git/MERGE_HEAD.

MERGE_HEAD written during merge of b5 into b6

Second, Git finds the base commit,

b4.

Third, Git generates the indices for the base, receiver and giver commits.

Fourth, Git creates a diff that contains the changes required to go from the receiver commit to the giver commit. In this case, the diff contains only one entry:

data/number.txt. Because the content for data/number.txt is different in the receiver, giver and base, the entry is marked as a conflict.

Fifth, the changes indicated by the entries in the diff are applied to the working copy. For a conflicted area, Git writes both versions to the file in the working copy. The content of

data/number.txt is set to:<<<<<<< HEAD

6

=======

5

>>>>>>> deputy

Sixth, the changes indicated by the entries in the diff are applied to the index. Entries in the index are uniquely identified by a combination of their file path and stage. The entry for an unconflicted file has a stage of

0. Before this merge, the index looked like this, where the 0s are stage values:0 data/letter.txt 63d8dbd40c23542e740659a7168a0ce3138ea748

0 data/number.txt 62f9457511f879886bb7728c986fe10b0ece6bcb

After the merge diff is written to the index, the index looks like this:

0 data/letter.txt 63d8dbd40c23542e740659a7168a0ce3138ea748

1 data/number.txt bf0d87ab1b2b0ec1a11a3973d2845b42413d9767

2 data/number.txt 62f9457511f879886bb7728c986fe10b0ece6bcb

3 data/number.txt 7813681f5b41c028345ca62a2be376bae70b7f61

The entry for

data/letter.txt at stage 0 is the same as it was before the merge. The entry for data/number.txt at stage 0 is gone. There are three new entries in its place. The entry for stage 1 has the hash of the base data/number.txt content. The entry for stage 2 has the hash of the receiver data/number.txt content. The entry for stage 3 has the hash of the giver data/number.txt content. The presence of these three entries tells Git that data/number.txt is in conflict.

The merge pauses.

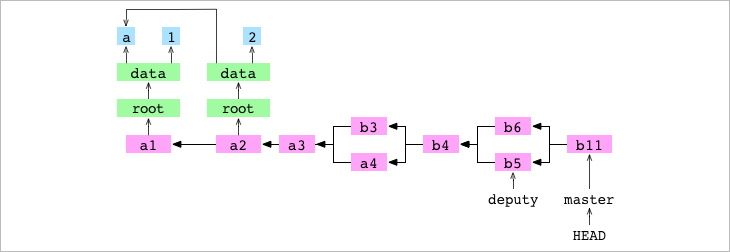

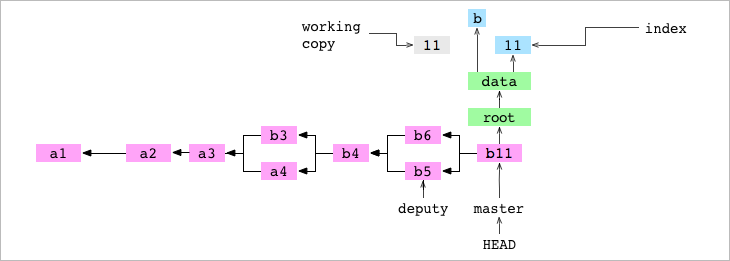

~/alpha $ printf '11' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

The user integrates the content of the two conflicting versions by setting the content of

data/number.txt to 11. They add the file to the index. Git adds a blob containing 11. Adding a conflicted file tells Git that the conflict is resolved. Git removes thedata/number.txt entries for stages 1, 2 and 3 from the index. It adds an entry fordata/number.txt at stage 0 with the hash of the new blob. The index now reads:0 data/letter.txt 63d8dbd40c23542e740659a7168a0ce3138ea748

0 data/number.txt ca7bf83ac53a27a2a914bed25e1a07478dd8ef47

~/alpha $ git commit -m 'b11'

[master 28118a0] b11

Seventh, the user commits. Git sees

.git/MERGE_HEAD in the repository, which tells it that a merge is in progress. It checks the index and finds there are no conflicts. It creates a new commit, b11, to record the content of the resolved merge. It deletes the file at.git/MERGE_HEAD. This completes the merge.

Eighth, Git points the current branch,

master, at the new commit.

b11, the merge commit resulting from the conflicted, recursive merge of b5 into b6Remove a file

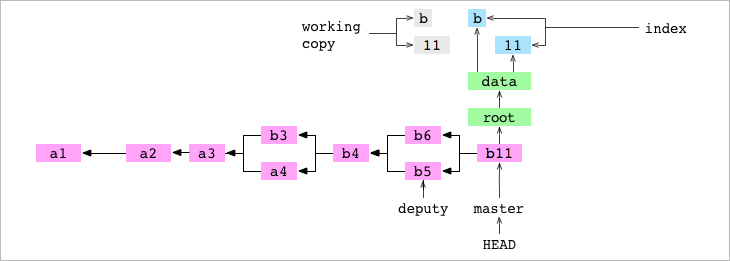

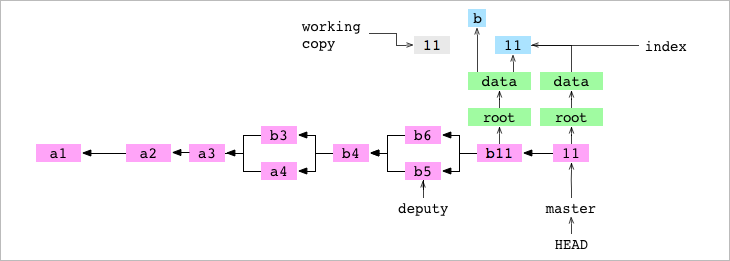

A diagram of the Git graph that includes the commit history, the trees and blobs for the latest commit, and the working copy and index:

The working copy, index,

b11 commit and its tree graph~/alpha $ git rm data/letter.txt

rm 'data/letter.txt'

The user tells Git to remove

data/letter.txt. The file is deleted from the working copy. The entry is deleted from the index.

After

data/letter.txt rmed from working copy and index~/alpha $ git commit -m '11'

[master 836b25c] 11

The user commits. As part of the commit, as always, Git builds a tree graph that represents the content of the index. Because

data/letter.txt is not in the index, it is not included in the tree graph.

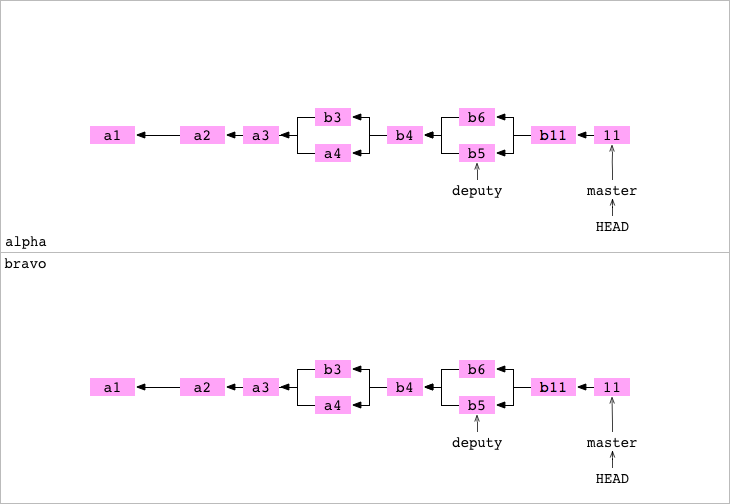

11 commit made after data/letter.txt rmedCopy a repository

~/alpha $ cd ..

~ $ cp -r alpha bravo

The user copies the contents of the

alpha/ repository to the bravo/ directory. This produces the following directory structure:~

├── alpha

| └── data

| └── number.txt

└── bravo

└── data

└── number.txt

There is now another Git graph in the

bravo directory:

New graph created when

alpha cped to bravoLink a repository to another repository

~ $ cd alpha

~/alpha $ git remote add bravo ../bravo

The user moves back into the

alpha repository. They set up bravo as a remote repository on alpha. This adds some lines to the file at alpha/.git/config:[remote "bravo"]

url = ../bravo/

These lines specify that there is a remote repository called

bravo in the directory at../bravo.Fetch a branch from a remote

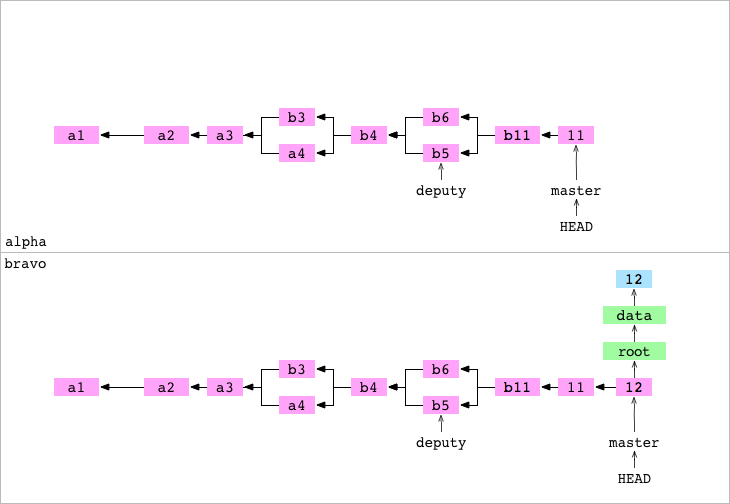

~/alpha $ cd ../bravo

~/bravo $ printf '12' > data/number.txt

~/bravo $ git add data/number.txt

~/bravo $ git commit -m '12'

[master 2870e6d] 12

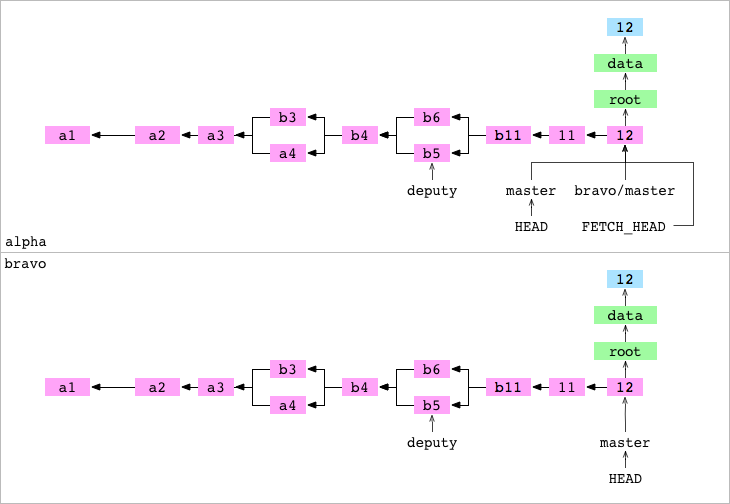

The user goes into the

bravo repository. They set the content of data/number.txt to 12and commit the change to master on bravo.

12 commit on bravo repository~/bravo $ cd ../alpha

~/alpha $ git fetch bravo master

Unpacking objects: 100%

From ../bravo

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

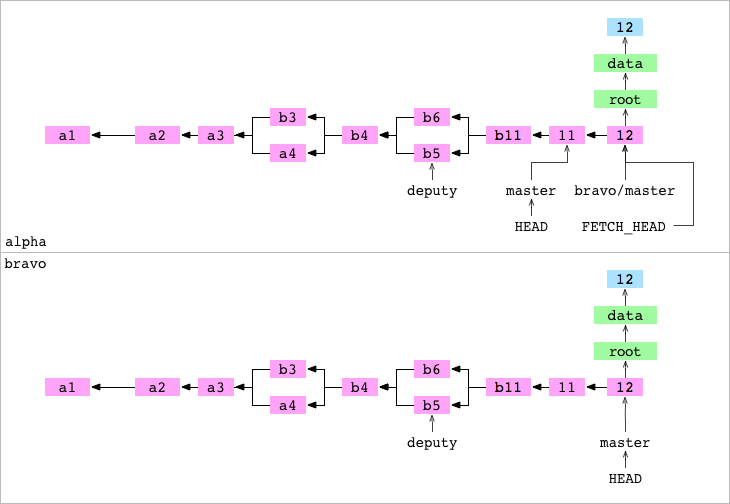

The user goes into the

alpha repository. They fetch master from bravo into alpha. This process has four steps.

First, Git gets the hash of the commit that master is pointing at on

bravo. This is the hash of the 12 commit.

Second, Git makes a list of all the objects that the

12 commit depends on: the commit object itself, the objects in its tree graph, the ancestor commits of the 12 commit and the objects in their tree graphs. It removes from this list any objects that the alphaobject database already has. It copies the rest to alpha/.git/objects/.

Third, the content of the concrete ref file at

alpha/.git/refs/remotes/bravo/master is set to the hash of the 12 commit.

Fourth, the content of

alpha/.git/FETCH_HEAD is set to:2870e6dda07ee04da3ad9e30da9bcaf0befbdbc6 branch 'master' of ../bravo

This indicates that the most recent fetch command fetched the

12 commit of masterfrom bravo.

alpha after bravo/master fetched

Graph property: objects can be copied. This means that history can be shared between repositories.

Graph property: a repository can store remote branch refs like

alpha/.git/refs/remotes/bravo/master. This means that a repository can record locally the state of a branch on a remote repository. Though correct at the time it is fetched, it will go out of date if the remote branch changes.Merge FETCH_HEAD

~/alpha $ git merge FETCH_HEAD

Updating 836b25c..2870e6d

Fast-forward

The user merges

FETCH_HEAD. FETCH_HEAD is just another ref. It resolves to the 12commit, the giver. HEAD points at the 11 commit, the receiver. Git does a fast-forward merge and points master at the 12 commit.

alpha after FETCH_HEAD mergedPull a branch from a remote

~/alpha $ git pull bravo master

Already up-to-date.

The user pulls

master from bravo into alpha. Pull is shorthand for “fetch and mergeFETCH_HEAD”. Git does these two commands and reports that master isAlready up-to-date.Clone a repository

~/alpha $ cd ..

~ $ git clone alpha charlie

Cloning into 'charlie'

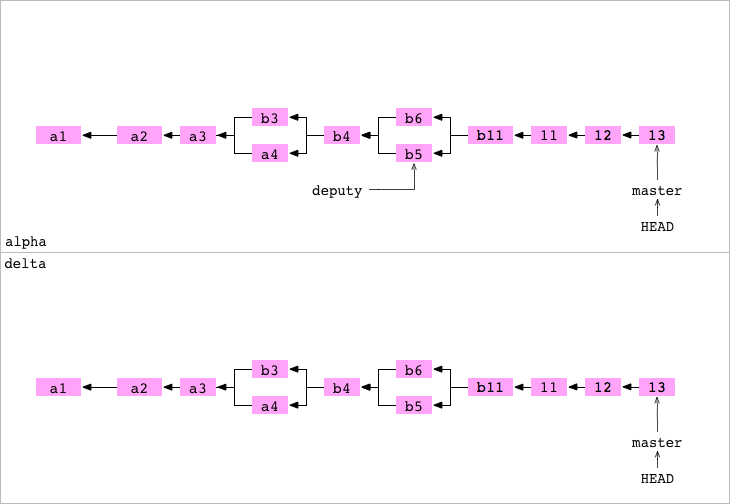

The user moves into the directory above. They clone

alpha to charlie. Cloning tocharlie has similar results to the cp the user did to produce the bravo repository. Git creates a new directory called charlie. It inits charlie as a Git repo, adds alpha as a remote called origin, fetches origin and merges FETCH_HEAD.Push a branch to a checked-out branch on a remote

~ $ cd alpha

~/alpha $ printf '13' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git commit -m '13'

[master 8b35db5] 13

The user goes back into the

alpha repository. They set the content of data/number.txtto 13 and commit the change to master on alpha.~/alpha $ git remote add charlie ../charlie

They set up

charlie as a remote repository on alpha.~/alpha $ git push charlie master

Writing objects: 100%

remote error: refusing to update checked out

branch: refs/heads/master because it will make

the index and work tree inconsistent

They push

master to charlie.

All the objects required for the

13 commit are copied to charlie.

At this point, the push process stops. Git, as ever, tells the user what went wrong. It refuses to push to a branch that is checked out on the remote. This makes sense. A push would update the remote index and

HEAD. This would cause confusion if someone were editing the working copy on the remote.

At this point, the user could make a new branch, merge the

13 commit into it and push that branch to charlie. But, really, they want a repository that they can push to whenever they want. They want a central repository that they can push to and pull from, but that no one commits to directly. They want something like a GitHub remote. They want a bare repository.Clone a bare repository

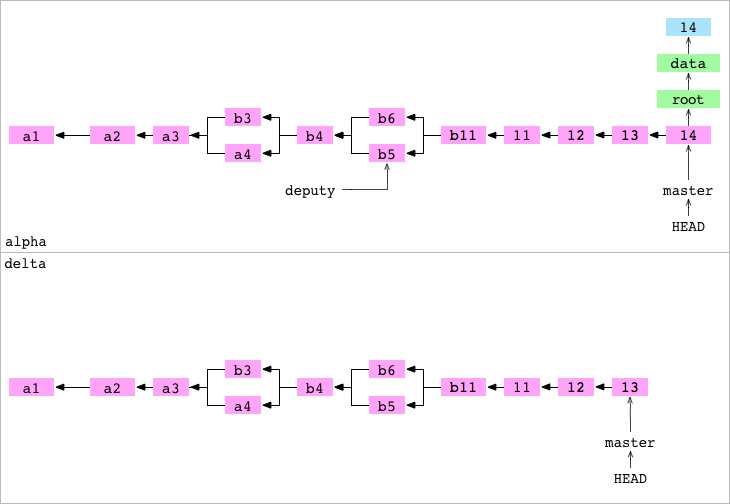

~/alpha $ cd ..

~ $ git clone alpha delta --bare

Cloning into bare repository 'delta'

The user moves into the directory above. They clone

delta as a bare repository. This is an ordinary clone with two differences. The config file indicates that the repository is bare. And the files that are normally stored in the .git directory are stored in the root of the repository:delta

├── HEAD

├── config

├── objects

└── refs

alpha and delta graphs after alpha cloned to deltaPush a branch to a bare repository

~ $ cd alpha

~/alpha $ git remote add delta ../delta

The user goes back into the

alpha repository. They set up delta as a remote repository on alpha.~/alpha $ printf '14' > data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git add data/number.txt

~/alpha $ git commit -m '14'

[master 02d1bb2] 14

They set the content of

data/number.txt to 14 and commit the change to master onalpha.

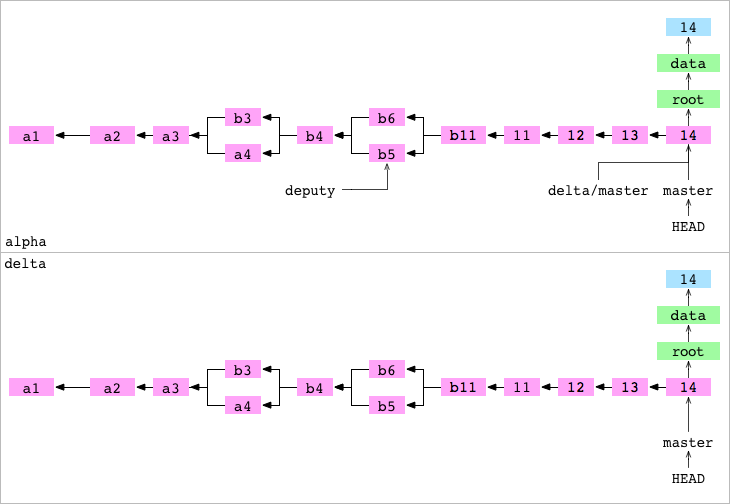

14 commit on alpha~/alpha $ git push delta master

Writing objects: 100%

To ../delta

8b35db5..02d1bb2 master -> master

They push

master to delta. Pushing has three steps.

First, all the objects required for the

14 commit on the master branch are copied fromalpha/.git/objects/ to delta/.git/objects/.

Second,

.git/refs/heads/master is updated on delta to point at the 14 commit.

Third,

alpha/.git/refs/remotes/delta/master is set to point at the 14 commit. This means alpha has an up-to-date record of the state of delta.

14 commit pushed from alpha to deltaSummary

Git is built on a graph. Almost every Git command manipulates this graph. To understand Git deeply, focus on the properties of this graph, not workflows or commands.

To learn more about Git, investigate the

.git directory. It’s not scary. Look inside. Change the content of files and see what happens. Create a commit by hand. Try and see how badly you can mess up a repo. Then repair it.- In this case, the hash is longer than the original content. But, all pieces of content longer than the number of characters in a hash will be expressed more concisely than the original. ↩

git prunedeletes all objects that cannot be reached from a ref. If the user runs this command, they may lose content. ↩git stashstores all the differences between the working copy and theHEADcommit in a safe place from which they can be retrieved later. ↩- The

rebasecommand can be used to add, edit and delete commits in the history. ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment